Feb 9 2021

Feb 9 2021B.C.’s old-growth forest nearly eliminated, new provincewide mapping reveals

The Narwhal

February 9, 2021

As old-growth logging continues unabated in most unprotected areas of B.C., one conservation organization decided to spend a year creating a detailed map that shows the province’s original forests have all but disappeared under pressure from industrialization

Many people imagine British Columbia as a province carpeted in forests, with giant old-growth trees, but a new interactive map reveals that little remains of B.C.’s original and ancient forests, showing logging and other industrial human activity as a vast sea of red.

The “Seeing Red” map, released Tuesday by the Prince George-based group Conservation North, took one year, 10 provincial and federal government datasets and $4,200 to pull together.

“The cumulative impacts of industrial forestry have never really been put on display for analysis or review,” Conservation North director Michelle Connolly told The Narwhal.

“And it became clear that if we wanted the truth, we would basically have to figure it out for ourselves.”

Connolly said one of the most striking things about the map is how little primary forest remains in B.C.’s interior, especially in the rare inland temperate rainforest where skyscraper cedar trees can be more than 1,000 years old and endangered deep-snow mountain caribou live in the spring and early winter, surviving on lichen found only on old-growth trees.

All B.C. old-growth forests are primary forests — also known as original, or primaeval forests — meaning they have never been logged. But not all B.C. primary forests are old-growth, as some have been affected over the centuries by natural disturbances such as wildfire.

Scattered amidst an enormous blaze of red, the map clearly depicts the few old-growth conservation opportunities that are left in the province’s interior, Connolly said.

“This part of B.C. has been ignored when it comes to discussions about old-growth forests.”

She pointed to three splashes of green in the eastern interior, toward the Alberta border, in areas outside federal and provincial parks. The comparatively small green swaths — known as the Walker Wilderness, the Raush Valley and the Goat River watershed — represent some of the last relatively intact and unprotected areas of rare interior temperate rainforest.

“These are really areas of focus for us because they still have values that people would like for nature,” Connolly said. “They’re home for wildlife, they have intact habitat, they’re diverse, they represent carbon assets, and they’re corridors that connect plant and animal populations.”

Zoom in even further, and much smaller, scattered splotches of green emerge in the blotchy red interior landscape, disclosing unprotected pockets of old-growth and original forests that could soon be logged in the Okanagan and the Kootenays, including in the Argonaut Valley, where conservation groups recently sounded the alarm about impending clear-cutting in endangered caribou habitat.

“Those are really important to protect because they function as lifeboats for biodiversity,” Connolly said. “We have landscapes here that are very fragmented.”

Map will ‘shock the heck’ out of British Columbians

Pacific Wild creative director Geoff Campbell said the high-resolution map, which allows people to zoom in anywhere in the province to view unlogged forests, will “shock the heck out of your average B.C. resident.”

“People around the world and even British Columbians have an idea of what B.C. is — it’s pristine, it’s wild. The true reality is that essentially all of B.C.’s old-growth forest has been eliminated, and all you need to do is to look at this map to see that,” Campbell said.

“The only places where you don’t really see habitat destruction happening is in the high, high mountains. Everything else is basically red.”

People always tell us they love our newsletter. Find out yourself with a weekly dose of our ad‑free, independent journalismYour emailYour emailSUBSCRIBE

Zooming into the Great Bear Rainforest area on B.C.’s central coast, inlets and waterways are etched in red, flanked by larger chunks of green that represent nearly three million hectares protected in parks and conservation areas.

“At Pacific Wild, we talk about how the ocean feeds the forest and the forest feeds the ocean,” Campbell said. “That is really where wildlife thrives, in these inlets, and that’s where you’re seeing all this industrial activity happening. It’s just heart-breaking … It shows that a place like the Great Bear Rainforest, which people see as pristine, really isn’t.”

Kukpi7 Judy Wilson, secretary-treasurer of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs and Chief of the Neskonlith Indian Band, said the map is a visual representation of First Nations concerns.

“We’ve decimated our old-growth forest and somebody has to be accountable,” Kukpi7 Wilson said in an interview.

“The old-growth policies unfortunately didn’t serve us well. It’s just allowed the removal of our old-growth.”

Tavish Campbell stands on a giant cedar stump on Gilford Island in the Great Bear Rainforest where old-growth logging is still taking place in some areas. Photo: April Bencze

First Nations call for transparency

The map’s release comes as the B.C. government dawdles on a fall election promise to implement 14 recommendations made by an old-growth strategic review panel led by foresters Al Gorley and Garry Merkel.

Gorley and Merkel called for a paradigm shift, saying old forests have intrinsic value for all living things and should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber supply. They also said many old forests are not renewable, countering the notion that old-growth trees can always grow back.

The two foresters recommended the B.C. government immediately defer development in old forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.”

In response, last September the NDP minority government announced old-growth logging deferrals for two years in nine areas, totalling 353,000 hectares.

Ten days later, the government called a snap election and the BC NDP took out campaign ads saying it had “protected” 353,000 hectares of old-growth.

But mapping subsequently revealed that much of the deferral areas were already under some sort of protection, had already been logged or consisted of non-forested areas.

Scientists Karen Price, Rachel Holt and David Daust estimated that only about 3,800 hectares of B.C.’s remaining productive old-growth was included in the nine deferral areas. Price and her colleagues also found that only 415,000 hectares of productive old-growth forests are left in B.C.

High productivity forests, where the biggest trees are found, contain the greatest biodiversity and are home to the most endangered species, such as mountain caribou, northern goshawk and fisher, a charismatic and reclusive member of the weasel family that, in B.C., dens only in five species of old trees.

Connolly said Conservation North wants people to be able to see where B.C.’s remaining old-growth is located. So, in tandem with the Seeing Red map, the group also mapped the 415,000 hectares of productive old-growth identified by Price and her colleagues. The second map, titled “Where is B.C.’s Remaining Old-Growth?” is also available online for free.

B.C.’s forestry practices came under renewed scrutiny this month when the Wilderness Committee discovered the new NDP majority government had sanctioned logging and road-building in 157,000 hectares of second-growth forests in the deferral areas it claimed it had “protected.”

Wilderness Committee national campaign director Torrance Coste called the government’s suggestion that it had protected 353,000 hectares of old-growth “factually incorrect and incredibly misleading.”

“At the bare minimum, people deserve to be told honestly by the government what is going on,” Coste told The Narwhal.

Kukpi7 Wilson said there is a lack of transparency and clear communication from the government about the old-growth deferrals, including what areas they cover, what criteria were used to determine the areas where logging was deferred for two years, and the total breakdown of old-growth areas eligible for deferrals.

She said the public needs to know the location of the most biodiverse, vulnerable areas that were neglected in the nine deferral areas and are in urgent need of protection.

“We need a transparent, accessible and easy-to-read way of understanding and analyzing the wealth of data around old-growth management in B.C.,” she said. “This is why an interactive map is so important.”

First Nations hope to expand on the map, she said, adding layers and datasets, “including further details around the areas that fall within traditional Indigenous territory and which companies are having the most impact in which high-risk areas.”

Old-growth protection opportunities in B.C.’s interior

When Valhalla Wilderness Society examined the government’s old-growth deferral area in the Incomappleux Valley east of Revelstoke, an inland rainforest with trees up to 1,500 years old, the society found only one-fifth of the 40,000-hectare deferral area consisted of old-growth.

Valhalla Wilderness Society spokesperson Anne Sherrod said parks and protected areas in the interior often don’t include highly productive low elevation valleys, where the biggest and oldest trees grow.

“We need a dramatic expansion of fully protected areas,” Sherrod said in an interview.

“When you look at that Seeing Red map, how can you question that? We have logged so much of our original forest, the primary forest. These forests are key for protecting biodiversity and mitigating climate change. These are two profound environmental disasters encroaching on B.C.”

Valhalla has been working for years to permanently protect wilderness along the north and east arms of Quesnel Lake — three puzzle-like pieces on the Seeing Red map that slide into the western boundaries of the Bowron Lakes, Cariboo Mountains and Wells Grey parks.

Sherrod described the proposed Quesnel Lake wilderness reserve as possibly “the largest and most intact body of inland temperate rainforest in existence today that is unprotected.”

The area is home to the endangered Wells Grey caribou herd, and has trees almost 2,000 years old.

“I don’t think the interior rainforest is getting nearly enough attention,” Sherrod said. “There needs to be a re-thinking of the province’s rainforest.”

Conservation North director Michelle Connolly, who has a background in forest ecology, surveys old-growth cedars in B.C.’s inland rainforest to estimate the amount of carbon the area holds. The ancient cedars pictured here are part of an old-growth management area where logging to facilitate road-building can take place. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

She said 72 per cent of the proposed Quesnel Lake wilderness protected area has been set aside as wildlife habitat areas for caribou, where logging isn’t permitted at the moment. But that’s not enough habitat to ensure the long-term survival of the Wells Grey herd, she pointed out.

“It doesn’t cover enough of the caribou habitat and, furthermore, it doesn’t cover the old-growth inland temperate rainforest.”

Almost 70 per cent of the ancient cedar and hemlock forests that would be protected in the proposed Quesnel Lake wilderness reserve has been left out of the wildlife habitat areas, which can be removed “with the stroke of a pen” if the endangered caribou herd disappears, Sherrod said.

“If they don’t create fully protected parks for future generations [after] decades of caribou planning in this province, that would leave us with nothing.”

Roy Howard is the president of the Fraser Headwaters Alliance, which has been working for decades to protect inland temperate rainforest in the Goat River watershed, part of the Fraser River headwaters. The upper reaches of the Goat River provide important spawning habitat for at-risk bull trout, while the watershed’s rare inland temperate rainforest supports endangered caribou, grizzly bears and rare lichens.

“The Goat contributes to the Fraser headwaters,” Howard said. “[It’s about] purity of water. To me, it’s just obvious that you protect things like that.”

The upper Goat watershed is currently off limits to logging because it has been designated as an ungulate winter range for endangered caribou, Howard said.

“That will only last as long as the caribou do, and we’re not optimistic about that.”

Howard said the alliance met with B.C. Environment Minister George Heyman in 2018 and made the case for protecting the Goat River watershed, but has not heard back from the government.

The unprotected Goat River watershed contains one of the few old-growth temperate rainforests left in B.C.’s interior. At-risk bull trout spawn in the upper reaches of the watershed, while old-growth forests are home to endangered caribou, grizzly bear and rare lichens. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Map shows intact forests in B.C.’s north

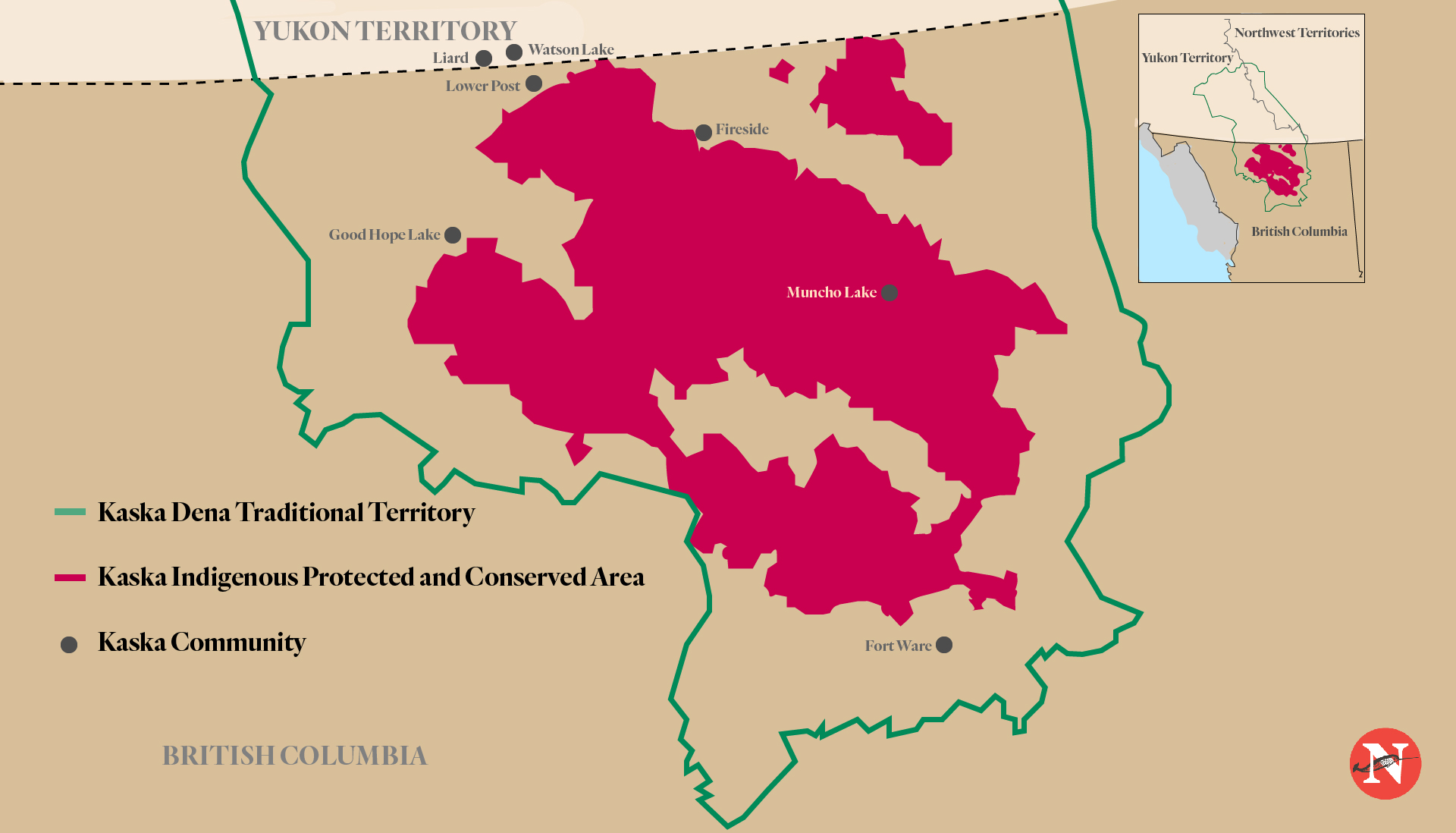

Some of the largest swathes of green on the Seeing Red map are in northeastern and northwestern B.C. One green patch in north central B.C. overlaps with a 40,000 square-kilometre area the Kaska Dena are working to protect as an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. Indigenous protected areas are gaining recognition worldwide for their role in preserving biodiversity and securing a space where communities can actively practice Indigenous ways of life.

The Kaska protected area would surround or connect to six existing protected areas, conserving watersheds and critical habitat for caribou and other species at risk of extinction while creating sustainable jobs.

Proposed Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Kukpi7 Wilson said protecting what little remains of B.C.’s original forests is an urgent First Nations Title and Rights issue. Old-growth trees are crucial to healthy ecosystems and Indigenous livelihoods and cultures, she pointed out.

Protecting old-growth and adequately working with and consulting with First Nations also aligns with B.C.’s commitment to implement its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, she said.

“The province must ensure decision-making and planning around old-growth forestry does not exclude First Nations and meets its commitment to the UN Declaration.”

The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs has said it wants to work with the province to implement an old-growth strategy that will enable conservation financing and the expansion of Indigenous protected and conserved areas, while also allowing First Nations to pursue economic alternatives to old-growth forestry — including businesses in cultural and eco-tourism, clean energy and second-growth forestry.

An aerial view highlighting extensive clearcut logging of productive old-growth forests in the Klanawa Valley on southern Vancouver Island, B.C. Photo: TJ Watt / Ancient Forest Alliance

In September, the union passed a resolution calling on the province to implement all 14 of Gorley and Merkel’s recommendations. The union said the recommendations would enable an improved old-growth strategy that will include and respect Indigenous Peoples, in keeping with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that B.C. has implemented through legislation.

In an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal, the B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said it plans to implement the 14 recommendations within the three-year timeframe recommended by Gorley and Merkel.

Asked when the government expects to take action on the recommendation to immediately defer development in areas where ecosystems are at “very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss,” the ministry said initial discussions are beginning with Indigenous groups, industry, labour and community leaders around identifying additional old-growth logging deferral areas.

“We heard loud and clear that the old way of protecting old-growth forests wasn’t working for anyone,” the ministry said. “We also know that getting this right is going to take time.”

The panel’s first recommendation is for government to government engagement with leaders from B.C.’s Indigenous nations, the ministry noted. “We know from discussions with a number of Indigenous groups that an engagement process of this scope and scale will require additional resources and we are taking steps to get the appropriate resources in place.”

Connolly said B.C.’s inland rainforest and boreal rainforest have largely been ignored in discussions about protecting the last of the province’s old-growth forests, even though a recent Forest Practices Board report sounded the alarm about the accelerating loss of biodiversity in the Prince George timber supply area in the province’s interior.

“These views that British Columbians get of our forests, both with our own eyes from the highway and via the messages that come out of industry and government, are carefully curated.”

The Forest Practices Board recommended that interior old-growth be promptly mapped and protected where it is most threatened by industrial logging. Connolly said that includes places like the Anzac Valley north of Prince George, which is home to old-growth spruce and subalpine firs and the endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd.

The board also recommended that the legal requirements for protecting biodiversity in the timber supply area be updated to reflect current ecological knowledge.

Connolly said Conservation North decided to map all original forests, not just old-growth forests, because all B.C. forests that have never been logged are now at risk, as biofuel and wood pellet industries expand quickly with provincial government support.

“What we’re seeing now is that the province has basically given permission to log lower productivity forests for things like pellets. We realized we had to broaden the umbrella of our concern. Here in this part of B.C., it’s not just the productive forests that are in trouble.”

Most people have driven down B.C. highways and looked out the window at a screen of trees, Connolly noted.

“And you can’t quite see what’s going on behind that strip of green but sometimes you’ll see a gap between the trees. These views that British Columbians get of our forests, both with our own eyes from the highway and via the messages that come out of industry and government, are carefully curated.”

She recalled taking a forestry course on how to conceal ugly industrialized landscapes from public view.

“We called that course ‘lying with the landscape 101.”

The Seeing Red map doesn’t hide anything, Connolly said. “It gives people a bird’s eye view.”

Read the original article